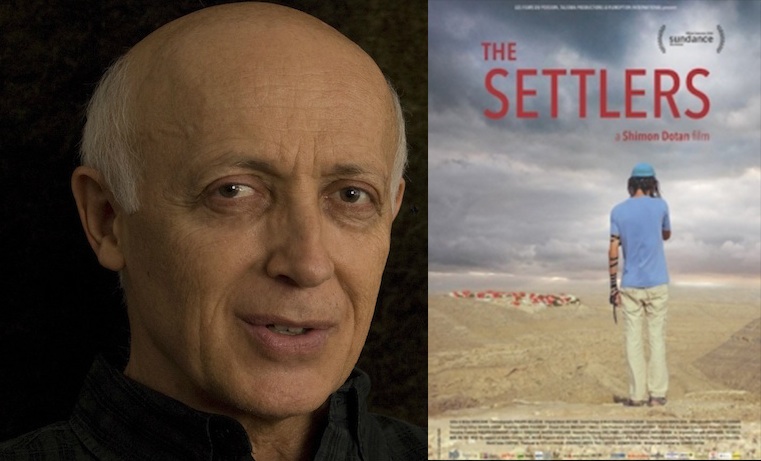

Shimon Dotan is an award-winning filmmaker with fourteen feature films to his credit. Born in Romania in 1949, he immigrated to Israel with his family in 1959. His films have won numerous awards, including the Special Jury Prize at Sundance (Hot House), the Silver Bear Award at the Berlin Film Festival (The Smile of the Lamb), numerous Israeli Academy Awards, including Best Film and Best Director (Repeat Dive; The Smile of the Lamb), and Best Film Award at the Newport Beach Film Festival (You Can Thank Me Later). Dotan’s most recent film, The Settlers, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2016 and has just been released in the United States. The documentary examines the history and the proliferation of Israeli settlements in Palestinian territory, a topic that continues to be highly relevant in the ongoing political climate of the Middle East. He spoke to us about his film, how it was received among different audiences, and the threat he perceives in the ongoing proliferation of Israeli settlements.

You were invited to present your film at Syracuse University’s “The Place of Religion in Film” conference later this spring. The organizers then retracted the invitation when the campus BDS (Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions) movement protested the screening of the film. What did you think about this episode?

A professor who was the organizer of the event was told that if I came to the conference to show the film, she and I would be very uncomfortable because of pressure from the BDS movement. At first I thought it's a joke, but it was not.I was very disturbed. So I show [her email] to some friends, and they show it to some other friends, and The Atlantic published an article about that, and it became a big thing online, and Syracuse University eventually apologized. We now have a date for a big event at Syracuse University in April.

The Settlers was shown at the New York Film Festival in the fall of 2016. What was that experience like?

The two screenings both sold out about two weeks before. The response was very good, people were very engaged. I found the Q & A after the film very much to the point. The objective I had when making the film [was] connecting with the audience. The film was screened last summer in Israel, in theaters all over the country to great success. People were extremely engaged and responsive there and it became the talk of the country at the time, so I was happy and surprised to see that the response crosses the ocean.

If the objective of the film was that it be discussed and talked about, what was the motivation for making it?

I’m Israeli and I’m terribly concerned about the future of the country and even more so, about the future of the character of the country. The settlement enterprise is, in my view, the main and most meaningful element that will impact the future of Israel. At first I thought that I’m going to do a study of the settlers themselves. Very soon I figured out that that would lead to a very limited understanding of the subject. So I have to give some historic background. But when you start doing that, you can’t give a partial historical background, so I did it more thoroughly, and I ended up with a film that covers three major elements. One is the history of the settlements, second is the religious and ideological background to the settlements, and third is the reality today in the settlements. All this somehow comes together and identifies how it all started, what the motivator was that drove them at the beginning, and from there I think we can extrapolate and understand where we are today and where this reality will lead. Either it can go on unchecked, or we need to do something in order to change this trajectory that, in my view, is catastrophic.

How is it catastrophic?

The settlement enterprise is a bubble that exists outside the legal system, the border system, the social system of Israel. It is actually the only reason that Israel clinches to the West Bank in such an uncompromising way. All this happens when these 400,000 settlers are living in the midst of 2.8 million Palestinians living under a separate set of laws, deprived of basic human rights within this territory with an economic status about one-twentieth of that of the settlers that live near them. This reality is explosive; it never worked in other places in the world and it won’t work here. The dominance of Israel over other people is instructive for the social moral fabric of the country, and I see a clear threat of disintegration from within of the state of Israel.

While making the film, was there anything that surprised you or moved you?

Studying the history of the settlements, I was surprised by the compliance and support for the settlements, and by the deception that the governments of Israel, from ’67 until today, were engaged in. They were enablers with, at times, zero ability to foresee where it could lead to and with a cynical and terrible intention when they did see where it goes. The governments are major players, enabling and supporting--overtly sometimes, and in a clandestine way other times--the beginning and the evolution of the settlements.

You were talking about reception of the film in Israel. The settlements are a controversial topic and there are many people with many different opinions. Was there any pushback? One Israeli newspaper said that your documentary showed a lot of very extreme settlers and that not everyone thinks in this way. What was your response to that?

There are 400,000 settlers. About 80 percent of them are what we call "quality of life" settlers. They're trying to live their lives in better conditions than they could have had in Israel proper. Housing is a big issue, quality of life is a big issue, and so forth. So they are not very much represented in the film, because my interest was in those who are driving this train, and not in the passengers. I focused specifically on those who are going to drive this train to the next station.

While you filmed this, did you see any potential solutions, any hope, anything that could change the course of the trajectory that you’re describing?

One of the speakers in the film, professor Moshe Halbertal, makes a very insightful observation in the film. He says that the settlers put in front of the Israeli people a very stark choice: Either they are going to fight the Palestinians forever or they're going to get a civil war. Choose. We have to find an agreement with the Palestinians where they will be getting self determination and we have two entities who will have to live by each other. Now, if there is a way to do it with the settlements staying there and every individual living in this territory and enjoying the same rights, then it may work. But to achieve that seems to me very implausible. I do believe that the only solution is a two state solution. There is no other solution. Maybe in the far future, if we can have some collaboration between the sides and even open borders, that would be wonderful. But for now, we have to respect the people who live among us and their right to self-determination. In the absence of that, nothing else can work.

What was your reception amongst people in the settlements?

At first they refused to talk to me. Somebody checked some previous work of mine and decided that I'm a leftist, so they distributed an email among the main settlers not to talk to me because I'm a deep leftist. But eventually I found my way in and I was able to reach people.

But my crew and I were attacked twice in a settlement. My photographer was beaten badly with an iron rod, and all our camera equipment and sound equipment was stolen, including the footage that was in it. In another instance, all the windows in my car were broken.

Were you expecting these negative responses to your presence in the settlements?

This is not a negative response. It's violence. This is crime. The truth is, no, I didn’t expect it. And I must say when I saw it I felt terribly betrayed because I am not engaged in violence when I'm making my voice heard or my position heard, and I would expect it to be the same on the other side. Without getting too much into it, that’s troubling.

The people who live in the settlements see them as their home. Did you find yourself sympathizing with the settlers in some way?

We’re talking about cities. There are cities with a population of sixty, seventy thousand people. It’s not a pioneer that goes and sticks a flag on a Palestinian territory. It’s completely transformed, so the mass of the people is like you and I, people who are trying to live their lives. They do not wake up in the morning and think, “oh did I harm a Palestinian today? I have to go to the synagogue and ask for forgiveness.“ That's not the case. People live their lives and they’re trying to do the best for their families but that’s a deceiving representation, because they do that on a burning territory, they do that on a ground that is shaking. We do not feel the earthquake but there's a tectonic movement and if we're all not mindful of that it will explode.

Do you feel that there’s nothing more to do about the settlements that are already there?

I did not look for a solution. It's a very complicated issue. If there is a will there is a way, but there is no will so there is no way. Both sides have to recognize this reality, but because Israel is the strongest entity in the region and one of the strongest in the world, I think it’s our responsibility to take the initiative, to act, not to wait for things to change.

Did you come away from this project with a sense of pessimism, or more determined for a call for action?

My action is the film. There is a sense of--I wouldn’t say pessimism, but there is a recognition that I feel a terrible waste, that so much energy and talent and in many cases the will of the individual is being wasted on an enterprise that is detrimental to the state that we all love.

Interviewed by Luisa Rollenhagen